Induced pluripotent stem cells

In 2006 Shinya Yamanaka published his ground-breaking research showing that adult cells could be re-wired into an embryonic-like state. These so-called ‘induced pluripotent stem cells’ (iPSCs) had acquired the remarkable ability to become any cell type in the adult body.

Cells lost to disease or injury could now theoretically be replaced using person’s own cells, and human cell types could be grown in the lab like never before. Just 6 years after publishing his work, Shinya Yamanaka went on to win the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine and the burgeoning field of iPSC research has continued to flourish ever since.

The history and applications of iPSC research

Pluripotent stem cells have the extraordinary capacity to become any cell type in the adult body, but unfortunately, only appear naturally for a very brief window during early embryonic development. In contrast, totipotent stem cells share this ability, yet can also contribute to the extra-embryonic tissues, such as the placenta and umbilical cord. At the other end of the spectrum, multipotent stem cells are found throughout development and adulthood, but can only produce a handful of different cell types.

Researchers have long been conscious of the potential applications of pluripotent stem cells. Early work by Evans, Kaufman, and Thomson showed that pluripotent stem cells could be isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos and cultured indefinitely in vitro1,2. These were termed ‘embryonic stem cells' (ESCs) and garnered a tremendous amount of controversy since discarded embryos from IVF were used to make them. During this period federal funding for stem cell research in the USA was massively withdrawn3. This provided an impetus to find another, less ethically controversial source of pluripotent stem cells.

Since the 1960s, thanks to pioneering work by John Gurdon, it has been known that all adult cells contain the complete genetic toolkit to make any other cell type. The only reason they don’t, is that they are epigenetically hard-wired through the development to become a specialized cell type. In the early 2000s, Shinya Yamanaka hypothesized against all conventional wisdom, stating that this wiring might be surprisingly simple to revert. He made an educated guess of 24 genes that he thought might be able to do it, later describing this as like ‘buying a winning lottery ticket’. Through a process of elimination, he found that just four of these genes, when over-expressed, were enough to rewire adult cells back into a pluripotent state. These genes (C-Myc, SOX2, KLF4, and OCT4) are known as the ‘Yamanaka Factors’, and the cells became known as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)4.

Since Yamanaka's breakthrough, the advances made using iPSCs have been unprecedented. Clinical trials have already begun in humans using iPSC-based stem cell therapies to treat age-related macular degeneration and Parkinson’s disease5,6. Disease modeling and drug discovery have now become more sophisticated than ever. Human cell types that were previously impossible to obtain by other means can now be derived from patient iPSCs with disease-specific genetic backgrounds. Developments in organoid and disease-on-chip technologies mean it is now possible to recreate tiny organ systems with different interacting cell types in a dish. Examples include miniature kidneys, modeling the blood-brain barrier, and modeling the loss of nerve-muscle connectivity in motor neuron disease7-9.

This provides an unprecedented level of insight into diseases and an innovative platform for drug discovery. In the future, it might even be possible to grow entire organs from iPSCs that could be transplanted into humans10.

Achieving top-quality iPSC cultures

Despite all the advancements in iPSC technologies, culturing iPSCs still remains a challenging and complicated process. There are now more options than ever for reprogramming methods, growth media, cell attachment substrates, dissociation reagents, and passaging techniques. Ultimately there is no one way to grow iPSCs. One lab using MEF feeders, mTESR medium, and colony passaging may have just as much success as another lab using feeder-free attachment substrates, Essential 8TM Medium, and single-cell passaging. What is important is that you find an approach that suits you, and more importantly, that you know how to properly evaluate the quality of your cultures.

1. Get to know your cell morphology

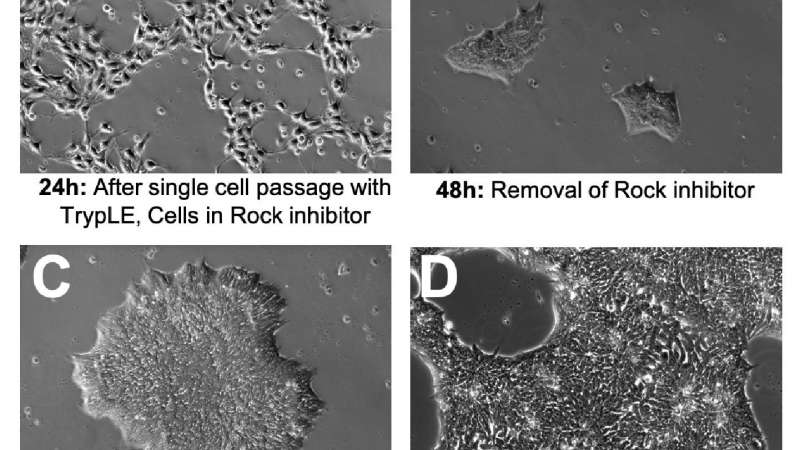

Observing the morphology of your iPSCs is the fastest and most effective way to monitor the quality of your iPSC cultures. It is normal for iPSC morphology to change at different stages of a culture. The following is an example of a normal four-day iPSC culture using single-cell passaging, iPSbrew, and laminin521 attachment substrate (Figure 1).

A - After single-cell passaging ROCK inhibitor is often used for up to 24 hours to improve cell attachment and viability. This can have a dramatic effect on cell morphology; cells will not form colonies and will take on a fibroblastic appearance (Figure 1A).

B - Upon removal of ROCK inhibitor, cells will shrink, cluster tightly, and form small colonies (Figure 1B).

C - Mature colonies should have a clearly defined border, tightly clustered small cells with uniform morphology (Figure 1C).

D - It is important to passage the cells at about 70-80% confluency before large colonies completely merge as this can lead to compromised viability and spontaneous differentiation (Figure 1D)11.

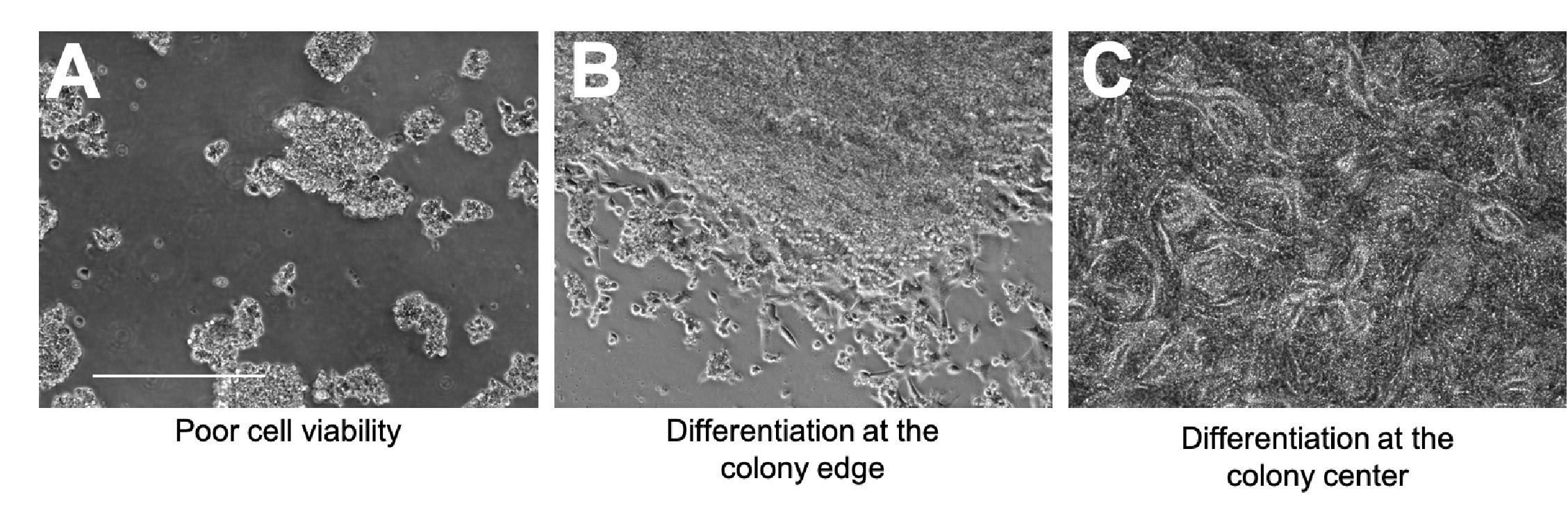

Looking out for signs of compromised cell viability and spontaneous differentiation is also incredibly important, as both of these can severely impact the quality of your iPSC culture.

A - Signs of compromised viability include cell shrinkage, cell rounding, and excessive levels of floating dead cells (Figure 2A).

B - Spontaneous differentiation can occur at the edge of the colony; fibroblastic-looking cells may start to grow outward and there will no longer be a clear colony border (Figure 2B).

C - Spontaneous differentiation can also happen at the center of the colony; cells will start to grow on top of one another and may start to form patterned structures (Figure 2C).

----------------

To evaluate the complete surface area of your cell cultures, multi-well plates, dishes, HYPERFlasks, and T-flasks, we recommend looking at the CytoSMART Omni.

----------------

2. Monitor the growth of your iPSCs

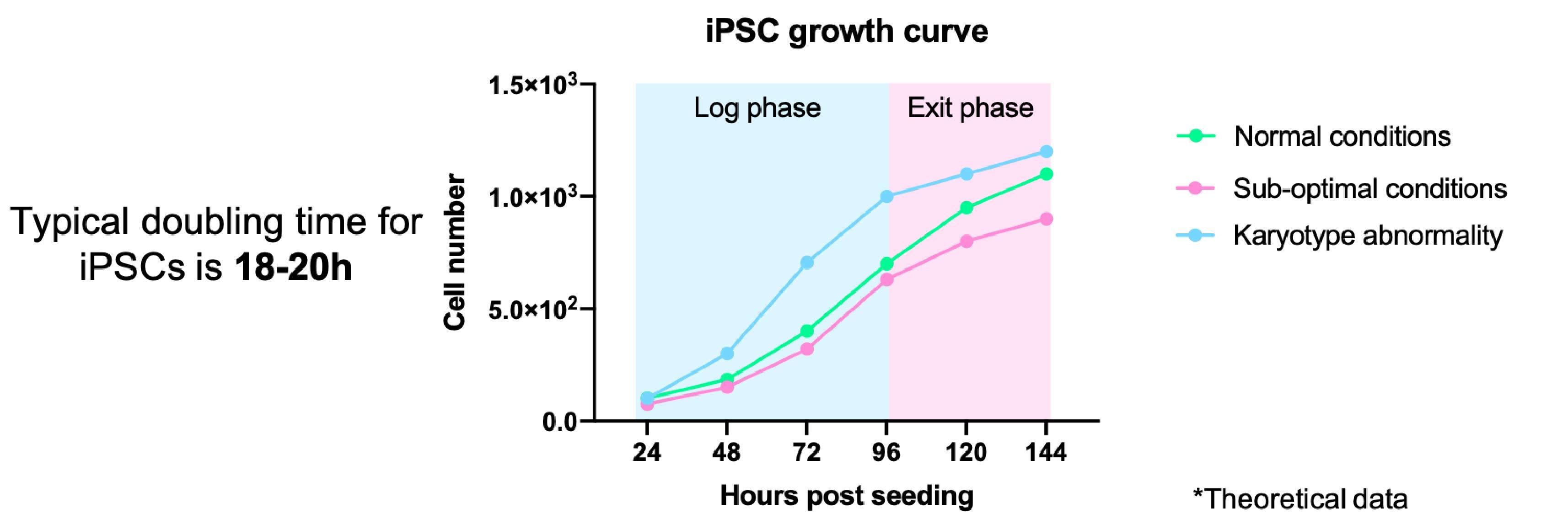

It is important to keep an eye on the growth rates of your iPSCs. Monitoring changes in the growth of your iPSCs can indicate problems with the culture, from sub-optimal culture conditions through to genetic/karyotypic abnormalities.

- This can be done formally through cell counting/measuring colony size and plotting a growth curve (Figure 3)

- Or it can be done more casually by noting the interval between passaging and the split ratios used

- Typically iPSCs double every 15-20 hours, however, this may vary depending on the reagents used and your cell line11

- iPSCs should always be maintained at the log phase of growth

----------------

For researchers looking to fully control and evaluate stem cell cultures, we recommend looking at the CytoSMART Lux2. This cell monitoring device contains software that provides real-time confluence detection, allowing immediate insight into the growth of your cell cultures.

-----------------

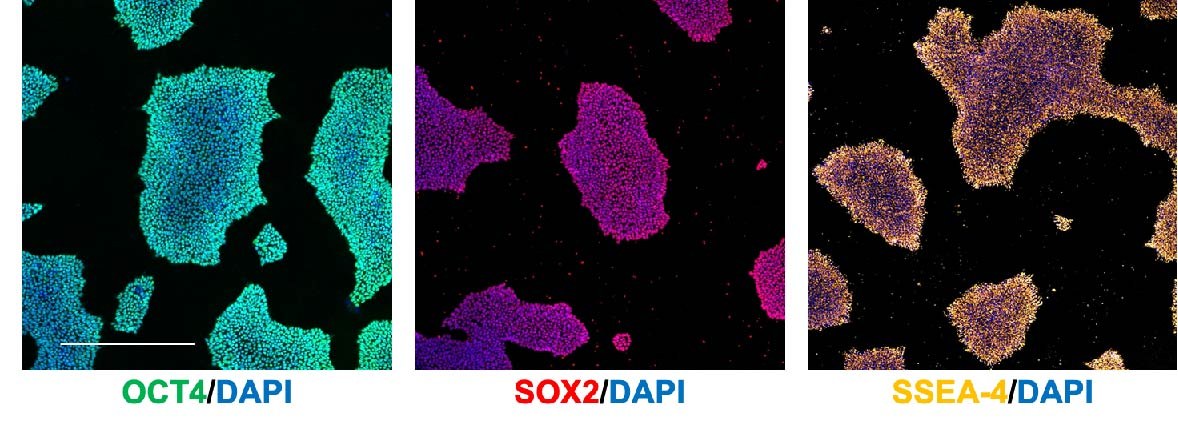

3. Monitor the pluripotency of your iPSCs

It is important to regularly immunostain/run a qRT-PCR for pluripotency markers to confirm that you are properly maintaining your iPSCs as pluripotent stem cells. Some common markers include:

- OCT4 (nuclear)

- SOX2 (nuclear)

- SSEA-4 (cell surface)

- Nanog (nuclear)

- TRA-1 60 (cell surface)

- KLF4 (nuclear & cytoplasmic

Immunostaining (Figure 4)/flow cytometry is preferable over qRT-PCR as it allows you to identify the percentage of pluripotent cells in the culture.

4. Assess the differentiation potential of your iPSCs

In conjunction with assessing the pluripotency of your iPSCs, it is also important to assess their differentiation potential. iPSCs may be pluripotent but can be more or less prone to differentiate down certain lineages due to epigenetic artifacts left over from reprogramming. As such it is important to assess this. A common method is to generate embryoid bodies (EBs) and stain for markers against the three germ lineages:

- Common ectoderm markers: PAX-6 and SOX2

- Common endoderm markers: CSCR4 and SOX17

- Common mesoderm markers: SM22a and CD144

5. Check your iPSCs for genetic/karyotypic abnormalities

Genetic and karyotypic abnormalities can occur at any stage of an iPSC culture. It is important to check for any abnormalities after initial reprogramming and at regular passaging intervals. Every 10 or so passages is a good benchmark. Such abnormalities can impact the growth kinetics of your iPSCs and may negate any conclusions you can draw from your experiments. G-banding is the most common way to assess the karyotype of your iPSCs, however more recently ‘Karyostat’ genotyping has been used as an alternative since it can detect much smaller chromosome abnormalities. Other genomic profiling approaches include HLA typing, STR genotyping, and CNV analysis.

6. The silent killer: Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma can wreak havoc with any form of cell culture. Unlike most other bacterial or fungal contaminations that are obvious within a matter of days, mycoplasma contamination can go completely undetected. Mycoplasma can severely compromise cell growth and proliferation, expose your cells to unwanted metabolites, and severely impact the levels of protein, RNA and DNA in your cultures negating the validity of your findings.

PCR detection tools are available and should be routinely carried out in iPSC labs. If contamination is found, it is crucial to dispose of all cultures with the contamination and get rid of associated reagents. Traditional antibiotics are ineffective against mycoplasma. However, some success can be achieved with long and intense exposure to plasmocin. However, this is not 100% effective12.

Summary

Culturing iPSCs is a challenging yet rewarding process. The ability to study any human cell type from any genetic background is unparalleled and the breakthroughs made using iPSCs will only continue to grow. While there may be many different ways to culture iPSCs, what is important is that you know how to robustly assess and maintain the quality of your iPSCs.

Related Products

There are currently no products tagged to this resource.